How food loss and waste impact people, planet, and profit

By Christian Yonkers

If food waste were a country, it would be the third-largest greenhouse gas emitter in the world.

Solving this problem is intuitive, seemingly simple: Stop wasting food. But a complex dance between economics and psychology creates plenty of nuance, and a nuanced problem requires nuanced answers. The good news is the world already has the tools it needs to stave the crisis. From simple habit changes to global policy shifts, the recipe for ending food waste for good is ready to cook up some truly world-changing benefits for climate, people, and the economy.

What is food loss and waste?

Food loss and waste (FLW) embodies the cumulative impacts of uneaten food across all stages of the food supply chain.

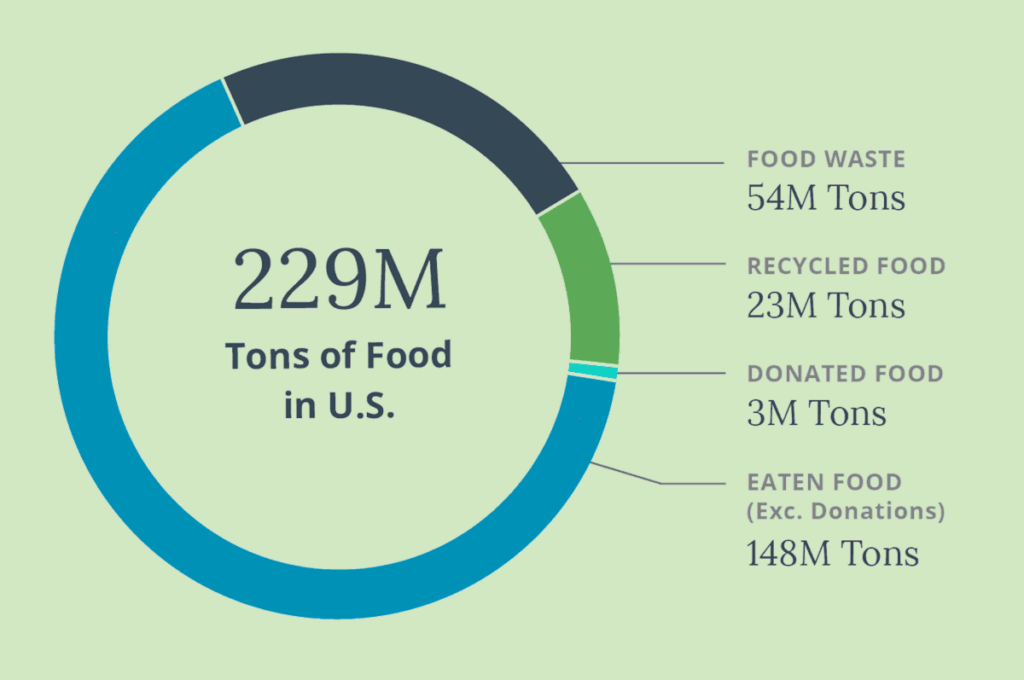

Up to 40 percent of U.S. food is wasted, with food scraps representing nearly 22 percent of all municipal solid waste. In the U.S., lost and wasted food range from 161 to 335 billion pounds each year. Globally, overmore than a quarter of agricultural land is used to grow food that goes uneaten. About half of this food is wasted in homes, restaurants, and other places that serve food, with fruits, vegetables, dairy, and eggs the most commonly wasted food items.

When organic waste is buried in a landfill, it undergoes anaerobic decomposition. This produces methane, a potent greenhouse gas with 28 times the global warming potential (GWP) of carbon dioxide. U.S. food loss and waste produces more emissions than the aviation industry, and globally, wasted food accounts for eight percent of the world’s carbon emissions. The cumulative impact of food loss and waste in the United States embodies:

- Agricultural land the size of New York and California combined

- 5.9 trillion gallons of blue water, roughly the amount consumed by 50 million homes each year

- 778 million pounds of pesticide

- 14 billion pounds of fertilizer—enough to produce all of the plant-based foods grown in the U.S. each year

- Enough energy to keep the lights on for 50 million U.S. homes for a year

- 170 million metric tons of carbon dioxide equivalents (CO2-eq) annually—the emissions of 42 coal power plants

Enough food to nourish 150 million people each year, more than enough to feed the 34 million food insecure Americans.

Want to learn more about the difference between Food Loss and Food Waste?

Reducing FLW reaps wide-ranging benefits affecting greenhouse gas emissions and climate change, freshwater resources, biodiversity and ecosystem services, soil and air quality, and our quality of life. For example, cutting FLW in half could reduce the U.S. food footprint by an area larger than Arizona and cut the emissions of 23 coal power plants. Drastically reducing or eliminating that wasted land frees up millions of acres of space for climate-friendly projects, like regenerative farming, reforestation, and renewable energy projects.

The financial case for saving food is the icing on the cake: All of America’s unsold or uneaten food adds up to 90 billion meals annually, valued at $418 billion or two percent of the U.S. GDP.

“If we could reduce loss and waste, you would see monetary benefits,” said Aaron Hiday, a compost program coordinator for the Michigan Department of Environment, Great Lakes, and Energy. “You’d see farmers and corporations saving more money, and you might actually see costs come down [for consumers] if there’s less waste because producers aren’t going to be pushed to produce more.”

Project Drawdown scores reduced food waste as the third-most viable climate solution in humanity’s toolkit, considering the cascading social and environmental benefits of tackling FLW. So why has this problem persisted (and even gotten worse)?

“We’re hardwired to store up, and then we also have another hardwiring that tries to eat only fresh, so we’re going to be less likely to use the stuff in the fridge because we could purchase something else,” said Hiday. “So we have waste in two ways: We store up, but then we don’t always utilize what we store, and we purchase even more, which compounds the waste problem.”

The problem transcends human genetics and to the very DNA of society. The modern food system is inherently wasteful by design, said Hiday, so coupled with biological desire to store up for hard times, humanity is burning both ends of the rope.

Policy and habit change to reduce food waste

Hiday says preventing food loss and waste requires both habit change at the consumer level and policy interventions.

“Most animals will take the easy way to do things,” he said. “We found an easy way to make waste disappear.”

Food runs along a complex international supply chain replete with waste, from the way food is grown and shipped to misleading portion suggestions and labeling. Most food produced today relies heavily on external chemical inputs to bring it from seed to harvest, thereby depleting the soil and greatly expanding the carbon footprint of farming, turning agriculture from a net carbon sink to a net carbon emitter. Consumer choice is no longer limited to proximity or seasonality, massaging in an artificial sense of variety and plenty while simultaneously masking the real cost of growing, shipping, processing, and storing food.

“We have the habit that if it’s easy to toss, we just toss it, and we have to change that mindset on the individual and corporate level.”

— Aaron Hiday

Official policy further enables the system. Farm subsidies favor input-intensive crops like corn, wheat, and soy while incentivizing a “get big or get out” doctrine for food production. And studies have shown that misleading food labels may actually lead to increased food waste. “Best by,” “use by,” and “sell by” dates are used to signify a product’s freshness, but they often lead consumers to assume perfectly edible food is spoiled.

Even if every household did its part to curb food waste, the system would still lose plenty of food on the field, in transport, during processing, and in the store. The solution to food loss and waste needs to address the problem’s complex, bifurcated institutional/personal nature.

ReFED identifies seven key areas ripe with potential for curbing food waste, starting at the beginning of the value chain until the end, with each step of the solutions journey provides varied financial, social, and environmental benefits that can be toggled on the ReFED Solutions Database:

- Optimize harvest

- Enhance product distribution

- Refine product management

- Maximize product use

- Reshape the consumer environment

- Strengthen food rescue

- Recycle what’s left

But the biggest challenge to circularity in food systems, said Hiday, isn’t the lack of innovation. Humanity has the tools to put unused food to good use, from planning shopping trips and making use of leftovers to tweaking the Farm Bill and utilizing emerging technologies.

The salient sticking point is a mindset shift.

“We have to change mindsets, and that’s the key challenge: Changing human behavior,” Hiday said. “We have the habit that if it’s easy to toss, we just toss it, and we have to change that mindset on the individual and corporate level.”

Co-opting the innate human desire to take the easy way could offer a powerful food waste solution. This means doing the hard work behind the scenes to make reactive approaches (like organics recycling) and proactive approaches (like limiting food waste from overstocking) the easiest choice for consumers and corporations.

“As long as you make it convenient, people will do it,” Hiday said. “Because we’re hardwired to search for the easiest way, if we don’t make it convenient, we won’t do it. If we do make it convenient, people are happy to switch.”

This is also where policy will play a role. It will take money and a lot of orchestration to make reducing FLW convenient for people, and all of this money and planning will require policy change, says Hiday.

Upcycled food can help feed a growing population without increasing additional strain on the environment.

The U.S. food system is built upon enduring legacies from the Great Depression and World War II. These policies—based on subsidies initially designed to ensure a lifeline for down-and-out farmers—started to apply more and more to large corporations during the “Green Revolution” following WWII. In the corporate race for bigger-cheaper-faster, the markets became saturated with cheap, easily tossed food.

“The true solution is that we have to change America’s food system,” Hiday said.

This year, advocates celebrated the passage of the Food Donation Improvement Act (FDIA). The Act modifies the 1996 Emerson Act by mandating the USDA provide updated guidelines and clarification on food donation. The FDIA also expands liability protections to large organizations (like grocery stores) donating food.

The FDIA was a rare instance of Congressional bipartisanship, a sign that food security is an issue that policymakers across the aisle can agree on. It;s now up to the USDA to update food donation guidelines, so the nation will have to wait and see the future effect of the FDIA in eliminating one of the country’s most serious social and climate issues.

Even at its best, the FDIA will need an arsenal of solutions for the change at-scale the country needs, and fast.

Solutions across the supply chain

FLW is best avoided by preventing excess food from going to landfill in the first place, and the best place to start is making use of ingredients that are already in the supply chain but would otherwise go to waste.

Upcycling refers to creating food products using ingredients that otherwise would not have gone to human consumption. For example, Do Good Foods pioneered a closed-loop system that upcycles un-donated, uneaten groceries into animal feed. The company’s proof-of-concept, Do Good Chicken, has diverted approximately 25 million pounds of surplus foods from entering landfills since launching in 2022, avoiding over 1,300 metric tons of emissions.

“As we continue to take action against climate change, upcycled food can help feed a growing population without increasing additional strain on the environment,” said Greener. “If just one in five chickens was a Do Good Chicken, we could solve grocery store food waste in five years. And that’s just chicken. Ultimately, Do Good Foods’ goal is to reduce the impact of animal proteins on the environment and plans to expand to other types of animal feed and product offerings in the future. The opportunity to make an impact is massive.”

Other upcycled food initiatives like Too Good to Go and Imperfect Foods rescue uneaten blemished food and resell it at a discount to customers.

If food and food scraps can’t be eaten, the next best choice is to harness microbial action in a planet- and people-positive way.

Near Flint, Michigan, a landscape company is turning local food scraps and lawn waste into valuable products and heat. Country Oaks Landscape Supply uses a small negative aeration digester to produce valuable compost and enough heat to warm two pole buildings and an uninsulated hoop house year-long.

This particular type of system is the way of the future, said Hiday; it’s modular and capable of processing vast types of organic waste, producing heat for warmth and valuable compost for the community as a co-benefit. Hiday foresees urban farmers using these systems to generate food in food insecure areas year-round, with hoophouses heated from these modular negative aeration systems.

“It will bring that hub-and-spoke model back to where it’s smaller, where it should be, to benefit the environment by reducing carbon emissions,” said Hiday.

Negative aeration digesters could be an important part of community composting programs. Nationwide, community compost programs Nationwide, community compost programs diverted an estimated 42.6 million tons of uneaten food, food waste, and yard trimmings in 2018. That’s despite just 27 percent of Americans with access to community composting programs.

Harp Renewables, an Ireland-based tech company, develops aerobic digesters that convert food and other organic waste into a dry, nutrient-rich fertilizer within 24 hours. 65 Harp digesters have been applied at various locations across the globe, resulting in over 14,000 tons of waste diverted from landfills and more than 41,225 tons of CO2-eq averted.

Data-driven solutions to FLW are part of this growing industry, too. ReFED is a nonprofit technology platform creating tools and resources encompassing a full supply chain image of U.S. food waste, as well as solutions to help reduce it and track progress. Winnow is a data analytics company helping the hospitality industry reduce food waste, helping to save over 36 million meals and prevent 61,000 tons of carbon dioxide equivalents.

Behind the scenes, these and other interventions represent a vast portfolio of institutional solutions required to create the policies, infrastructure, and markets for reducing food loss and waste—and hopefully, making it much easier to slash waste at the consumer level.

Composting at Home helps to reduce our trash and build healthy soil.

What consumers can do

“Americans view reducing food waste as one of the most impactful ways they could help fight climate change,” said Greener. “There is an opportunity to further educate consumers on the benefits of upcycled food and how small changes within our lives can make a huge difference.”

Food waste is the number one material in American landfills, the culmination of countless small decisions to purchase food, let it go unused, and throw it away. Small lifestyle changes can save households up to $370 per person, per year, on top of social and environmental benefits:

-

- Take stock. Creating an inventory of existing food in the pantry, refrigerator, and freezer helps prevent overbuying at the store.

- Plan ahead. Meal plans not only reduce wasted food, but are also a great way to practice food mindfulness and promote healthy eating habits such as portion sizing and increasing vegetables in meals.

- Storage. Storing food properly (especially perishable food like fruits and vegetables) ensures they don’t spoil prematurely.

- Leftovers. Leftover food should be refrigerated and eaten immediately. It can also be frozen for later use or creatively utilized in new dishes.

- Compost. Some food waste is inevitable, but in a circular economy, waste becomes a valuable input. Backyard composting is a great way to divert food scraps from the landfill and convert them into nutritious compost for gardens. Some cities host community composting programs for those unable to compost their food scraps at home.

- Advocate. Become an advocate for policy and initiatives that reduce food waste and promote compost access. The US Composting Council provides resources for key policy issues to promote composting and how to get involved.

Stopping food loss and waste will require both systemic institutional reforms and individual lifestyle changes. The social and environmental benefits are immeasurable, and because of the low cost needed to tackle FLW, it’s low hanging fruit with an outsized impact delivering multiple shots on target for the climate and people.

Digesters, data solutions, and upcycled food initiatives are just the tip of the spear in the effort to mitigate food loss and waste while still feeding the world sustainability and justly. Existing technological and policy interventions and at-home habit change are solutions in a vast suite of tools shifting the global narrative on uneaten food and ending wasted food for good.

Food loss and waste (FLW) estimates

This chart compares food loss and waste (FLW) estimates, by food category and supply chain stage, from the Food and Agriculture

Organization (FAO) of the United Nations for the North America and Oceania (NAO) region to those from the United States Department of

Agriculture (USDA) for the United States only. The rows show FLW by supply chain stage, and the columns show FLW by food category.

FLW at the consumer stage is the greatest, followed closely by FLW at the primary production stage. By weight, fruits and vegetables are the most lost and wasted food category.

Want to learn more or get involved? Check out these resources!

ReFED: Advancing data-driven solutions to fight food waste.

Be an Advocate! Use Your Voice for Compost