“There’s a whole ecosystem happening in the soil that we barely understand.”

– Joan Maloof, Old-Growth Forest Network

Missing the Old-Growth Forest for the Trees

Tree planting is all the rage but will do far less good than protecting the older forests we already have.

Planting trees is the single most popular solution for addressing climate change there is, widely championed by Republicans, Democrats, corporations, environmental NGO’s and climate experts alike.

But did you know that existing forests remove over 30% of manmade carbon dioxide emissions each year? That they store trillions of tons of carbon in their branches, trunks, roots, and soils? Or that the older a forest gets, the more carbon it absorbs and sequesters each year?

We sat down with Joan Maloof, founder and CEO of the Old-Growth Forest Network, to set us straight.

A conversation with Joan Maloof

TCP’s Jack Stephenson speaks with Joan Maloof of the Old-Growth Forest Network.

The Old-Growth Forest Network was founded in 2011, but Joan’s journey began long before that. She was a professor and scientist who spent most of her life studying plants. In 2007, she wrote her first book, Teaching the Trees: Lessons from the Forest, a collection of essays on good forest stewardship.

The book opens with a haunting description of Joan visiting a virgin forest that had never been logged. Her readers, many in the eastern part of the U.S., began asking how they could have a similar experience.

Sadly, there are very few old-growth forests left in our country and almost none on the East Coast. Less than 5% of forests in the West and 1% in the East are considered true old-growth. Searching for a way that other people might have the same experience she did, Joan wrote her second book, Among the Ancients: Adventures in the Eastern Old-Growth Forests. Each chapter describes an old-growth forest in 26 eastern states, along with directions on where to find them.

These early writings and experiences formed the basis of what would one day become the Old-Growth Forest Network.

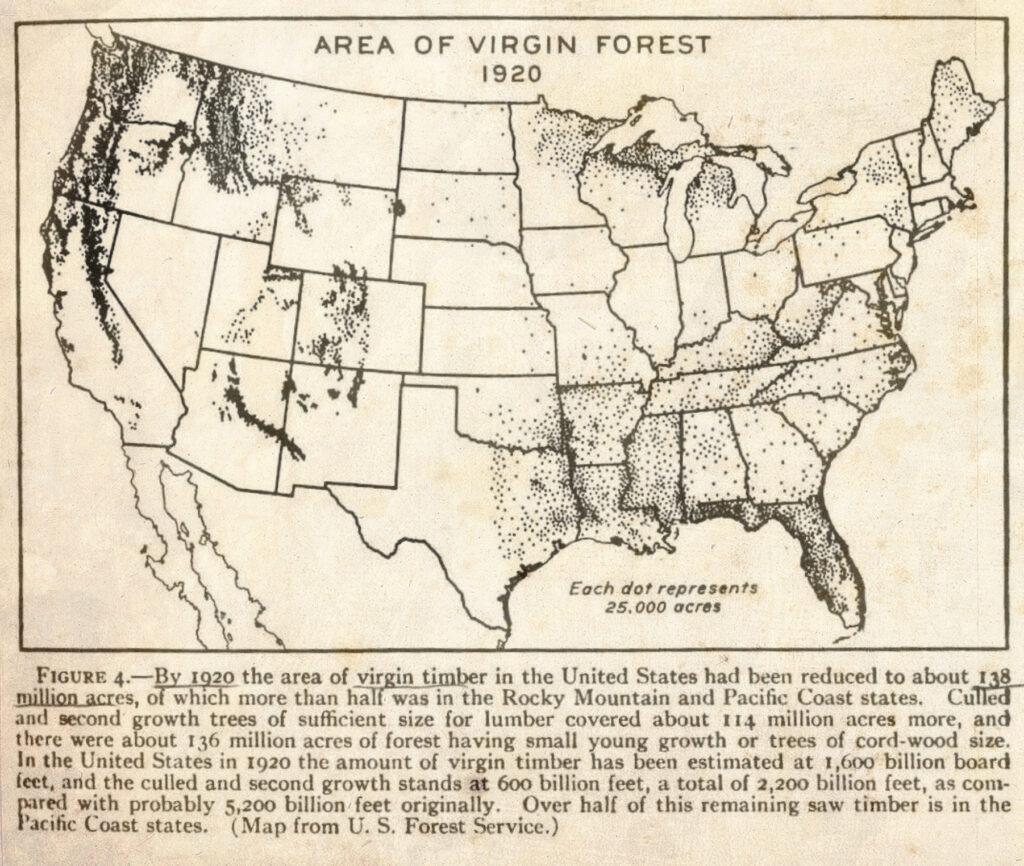

Joan shared with us a bit of history on U.S. forests, starting with the first settlers who came here from Europe. When they arrived in North America and saw seemingly endless forests they were in awe. Most of the virgin forest in Western Europe had been cut down. They promptly set up operations to clear-cut these old-growth forests and send the timber back home.

Says Joan, “In a very short amount of time, we went from 60% of our forests being old-growth to about 5%.”

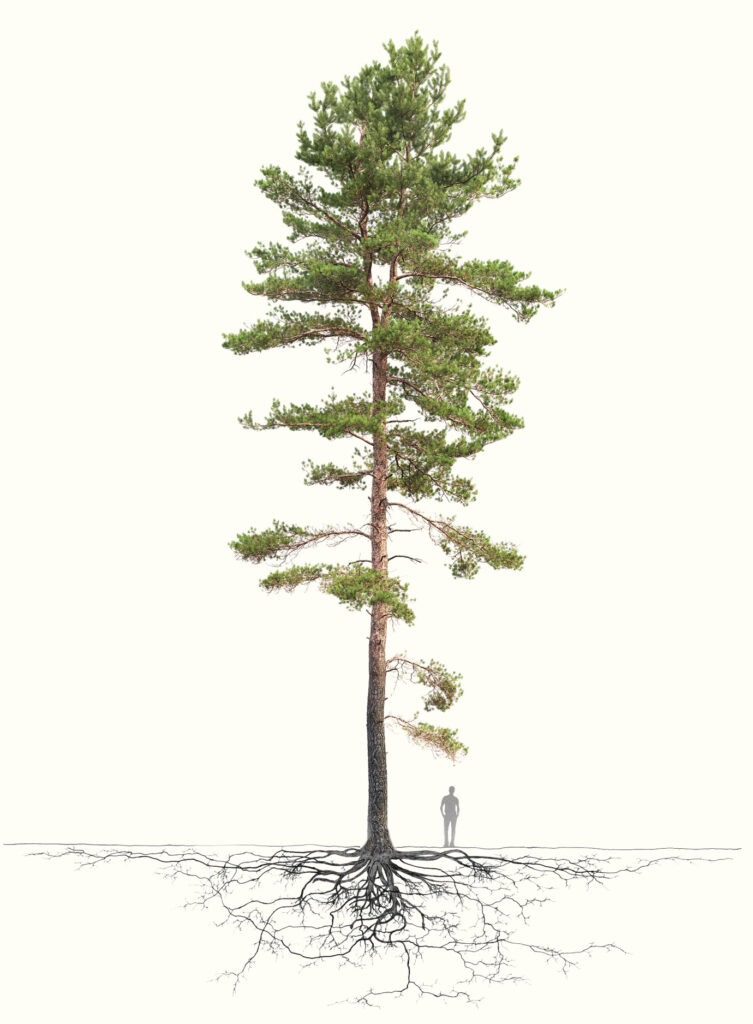

This matters deeply from a climate perspective. Carbon dioxide is removed from the atmosphere and stored both above ground in a tree’s branches and trunk, but most of it below ground in the tree’s roots and soil. The older a tree gets, the more carbon it stores.

“There’s a whole ecosystem happening in the soil that we barely understand”, Joan told us. Soils provide nutrients, moisture, and chemicals to support a vast array of organisms and vital processes that keep these interdependent systems alive and functioning.

The map displays the regional distribution of stand age, based on FIA data from 2007–2012Of 3289 plots in the study region, only 17 (approximately 0.5%) are 150 years old or older; 299 plots (approximately 9.1%) are 100 years old or older. SOURCE: MDPI

When a tree is cut or burned down and its roots are destroyed, the exposed soil oxidizes in the sunlight, and releases even more carbon dioxide. “Also”, Joan explains, “much of the mycelium, and other organisms that were part of the ecosystem being nourished by the fallen trees will die. And when they die, more carbon dioxide will be released into the air.”

This is not understood by most people because they have been led to believe that replacing older trees with newer ones absorbs more CO2 because younger trees grow faster. While younger trees do indeed grow faster, it can take hundreds of years for a new tree to absorb the carbon that gets released by cutting down the older trees. Older forests absorb significantly more carbon than newer trees, just at a much slower rate.

The older a forest is, the more carbon it can hold. According to Joan, if you calculate the carbon that a tree is taking out of the atmosphere, a “larger tree can remove as much carbon in one year as it takes a young tree 50 years to remove. If we “keep cutting trees down that reach less than the ideal 50-100 years of age, when they are at their peak for absorbing carbon, we are severely undermining the carbon-storage potential of our forests.”

So it turns out that one of the most popular and widely heralded solutions to climate change might not be such a great solution after all—unless we stop harvesting older trees at the same time. The overriding message is that we need to do both simultaneously, with an eye on reducing carbon dioxide emissions and maximizing long-term carbon storage.

If we stop cutting down standing forests and let them grow to full maturity, we can absorb and store significantly greater amounts of carbon. Joan’s big takeaway from her years of research? Increasing the average age of forests is one of the most effective ways to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, while providing a wide array of benefits to local communities and the planet.

The struggle we often face as human beings and climate policymakers alike is that we tend to be action-oriented. We have a hard time recognizing that NOT doing something is sometimes the best answer.

Keeping existing forests standing and healthy is one of the very best things we can do to fight global warming.

Find a Network Forest

The forests in the Old-Growth Forest Network are chosen because they are among the oldest known forests in their county. They have formal protections in place that ensures that their trees and ecosystems are protected from commercial logging. All network forests are open to the public so that everyone can experience them for recreation and personal well-being.

Did you know?

Redwoods can store up to 2,600 metric tons of carbon per hectare (2.4 acres)

RELATED ARTICLES:

Become a Climate Actionist

#climateactionist

One of the first things you do to start your Climate Actionist journey is connect with, engage with, and even join leading climate organizations. At The Copernicus Project, we are committed to only sharing information and resources from organizations, experts, companies, communities, and people that we have personally researched and trust. The following list is a great place to start. We’ve broken it out by category, so you can hone in on the things you are most interested in.

In the coming weeks and months, we’ll have more ways for all of us to be actively involved in finding and supporting nature-based climate solutions. So stay tuned and sign up below to get notifications when we publish new content.