“ The fact that we have older trees and ecosystems means that we’re storing very high amounts of carbon. At the same time, we have degraded sites that could be returned to productive forests through reforestation. ”

– Dr. Ann Bartuska, former chief scientist for the USDA

From Conservation to Carbon: The Evolving Role of the U.S. Forest Service

In the late 1800s, the United States was growing fast. The nation was selling off publicly owned land to private citizens for farming, ranching, and railroad construction. Americans saw their forests as a limitless resource for economic growth and a personal reward for hard work and entrepreneurship.

“Go West young man,” wrote newspaper editor Horace Greeley, “go West and grow up with the country.”

John Muir and John Burroughs, full-length portrait, standing on snow 1899 SOURCE: Library of Congress

Others, though, saw the rampant destruction of forests, wildlife and pristine wilderness as an imminent threat. A small group of prominent men — led by Teddy Roosevelt, Gifford Pinchot, George Bird Grinnell, Aldo Leopold and others — felt the urgent need to protect and manage the country’s natural resources for future generations.

The creation of the U.S. Forest Service was the first — and by far the boldest — attempt to declare vast swaths of forest off limits to unfettered commercial exploitation.

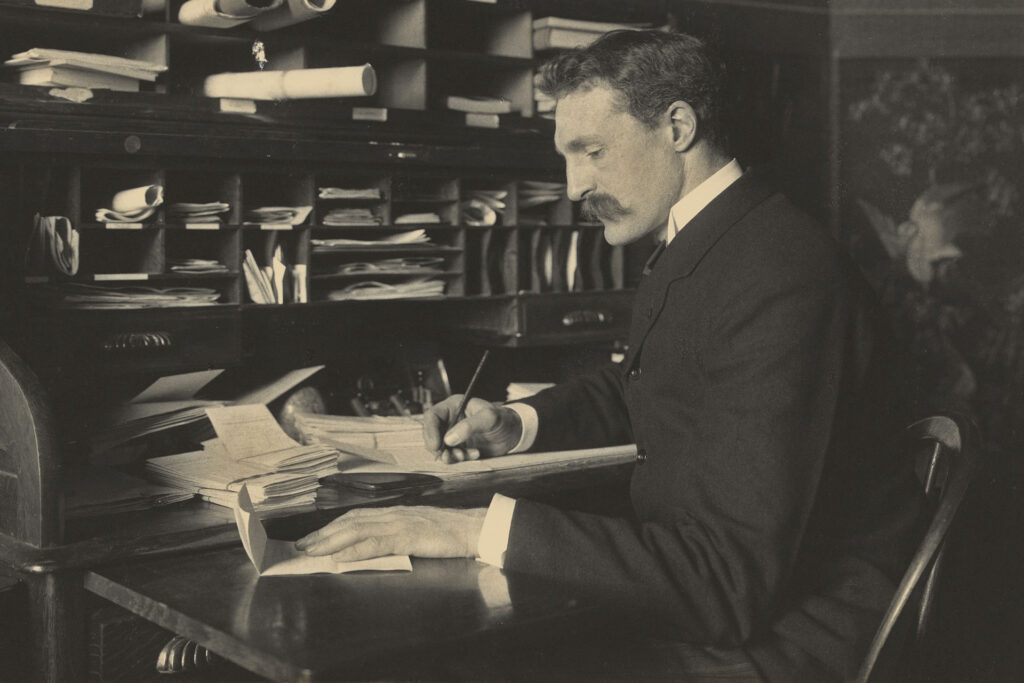

Gifford Pinchot, America’s First Forester

In 1905, Congress established the U.S. Forest Service as a division of the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) — a move that marked the height of the Progressive movement and a defining moment in Theodore Roosevelt’s presidency.

The new federal agency was charged with mapping, maintaining, and protecting the nation’s forests. Gifford Pinchot, called “America’s first forester,” was a close friend of President Roosevelt and headed the agency. He and Roosevelt believed strongly that the government must regulate public lands and manage the country’s forests to maximize their long-term productivity. Pinchot helped popularize the word “conservation” — meaning wise use of our natural resources.

Gifford Pinchot seated at his desk. SOURCE: Library of Congress

“Without natural resources, life itself is impossible. From birth to death, natural resources transformed for human use, feed, clothe, shelter, and transport us. Upon them we depend for every material necessity, comfort, convenience, and protection in our lives. Without abundant resources prosperity is out of reach.”

– Gifford Pinchot

Pinchot headed the USFS from 1905 to 1910. In these five years, he restructured the agency and professionalized management of our national forests. He greatly expanded their number and size — aided in no small part by Roosevelt’s liberal use of executive orders. By 1910, the total land area managed by USFS had nearly tripled, growing from 60 reserves covering 56 million acres to 150 reserves covering 172 million acres.

Pinchot is regarded by many as the father of the American conservation movement. His work set the tone for effective organization, management based on scientific principles, and conservation of the country’s natural resources.

Expansion of the USFS Mandate

Recreational visits to national forests and parks shot up after World War II as American families hopped in their automobiles and boarded trains to enjoy the country’s scenic beauty. During the mid-20th century, hunting, fishing and camping were among the most popular activities drawing visitors to national forests.

The Roosevelt administration took a utilitarian view of public lands, attempting to provide the greatest good for the largest number of people in perpetuity. Aldo Leopold, who later became one of America’s foremost environmental scholars and advocates, fought to protect nature for nature’s sake.

Fire patrol of the US forestry service, circa 1910. SOURCE: Library of Congress

Leopold worked for the Forest Service from 1909 to 1928 and coined the term “wilderness”. In the spirit of John Muir, he advocated making preservation a fundamental pillar of U.S. public land management,

Early in his career, Leopold was charged with hunting bears, wolves, and mountain lions in New Mexico and Arizona to protect local ranch livestock from predation. One day, after fatally shooting a wolf, Leopold became transfixed by a “fierce green fire dying in her eyes.” This deeply affected his ideology around ecological land management. He challenged the concept of human dominance over ecosystems and stressed the importance of predators in the balance of nature. His advocacy resulted in the return of bears and mountain lions to New Mexico wilderness areas.

The mission of the Forest Service has also expanded. By the 1950s, national forests no longer provided sufficient resources to support a rapidly expanding American economy. The Multiple-Use Sustained Yield Act of 1960 directs the Secretary of Agriculture to manage national forests as a “multiple-use” resource, providing a wide array of benefits to the public — such as timber, livestock, hunting, recreation, scenic beauty, and wildlife.

Today there are 154 national forests and 20 national grasslands managed by USFS. From Allegheny National Forest in Pennsylvania to Willamette National Forest in Oregon, these reserves comprise 190 million acres of land, an area larger than the state of Texas.

The multiple-use mandate still stands even as the U.S, population has doubled and annual visits have skyrocketed. Today, the USFS supports sustainable management of roughly 500 million acres of private, state and tribal forests, grasslands, wildlife, and waterways.

“A wilderness, in contrast with those areas where man and his own works dominate the landscape, is hereby recognized as an area where the earth and its community of life are untrammeled by man, where man himself is a visitor who does not remain. ”

– Howard Zahniser, primary author of the Wilderness Act

In 1964, Congress passed the Wilderness Act, signed by President Lyndon Johnson, to preserve and protect certain lands “in their natural condition” and thus “secure for present and future generations the benefits of wilderness.” The National Wilderness Preservation System is a network of over 109 million acres – an area larger than the state of California – comprised of 760 wilderness areas administered by the federal government.

USFS and Climate

As we face the climate crisis, forest conservation is more critical than ever. Even our healthiest forests are threatened by climate change. We spoke with Dr. Ann Bartuska, former chief scientist for the USDA, to learn more about the state of U.S. public forests.

“The positive thing is that the forest estate has been expanding,” Dr. Bartuska told us. “We’ve been able to see a return from agricultural lands into forest lands.” As agricultural productivity has improved, marginal lands once degraded by agricultural pressures have been allowed to transition back to forest.

The bad news is that urban expansion, logging, and ecological degradation are putting severe stress on public forests. Deforestation from development and timber harvest has taken a serious toll — especially on western, old-growth stands that sequester huge quantities of carbon. Over the past two decades, these forests have become increasingly vulnerable to droughts, fire, insects, and disease, all of which are exacerbated by global warming.

SOURCE: USFS

Fire suppression has been a core focus for the Forest Service since its formation. The Great Fire of 1910 burned 3 million acres of forested land in North Idaho and Western Montana. Rather than let natural fires burn, the Forest Service has focused on prevention. Smokey the Bear is one of the most widely recognized icons in the country, thanks to The Wildfire Prevention Campaign, the longest public service announcement campaign in U.S. history. Instead of letting natural fires burn, public agencies have tried to extinguish blazes as fast as possible.

A century of fire suppression has made our forests far less resilient to wildfires. Fire plays a critical role in forest ecology and is essential for clearing the understory and maintaining low stand-density — two contributors to overall forest health. Suppressing natural fires causes forests to become overcrowded and, as they dry out, more susceptible to out-of-control wildfires.

“We now know that we don’t want to have full suppression, we want to be more aggressive about thinnings,” explained Dr. Bartuska.

This map displays current data on wildfires in the US. SOURCE: Esri, USGS, HERE, Garmin, FAO, USGS, EPA I NOAA, National Weather Service

The Forest Service has recently started reintroducing fire to forests through controlled burns and educating the public about the role fire plays in protecting local ecosystems. But as temperatures rise, so will the frequency and severity of natural disasters.

“We have more extreme events than we’ve ever had. Being able to manage in that extreme, almost chaotic, environment is becoming a challenge,” said Dr. Bartuska.

In 2010, the Forest Service established a new position: Chief Climate Advisor. Using climate science and carbon accounting to drive policies and action marks a major shift in Forest Service management priorities. Each national forest has since developed its own climate adaptation plan, outlining specific goals for responding to climate change. Climate mitigation and protecting healthy old-growth forests have recently been added to the list, as well as replanting and restoring forests that have been damaged.

SOURCE: USFS

Overdevelopment, profit-oriented timber harvesting, poor ecological management, and climate change threaten the benefits provided by multitude of ecosystem services. “Natural capital” — an approach that ascribes economic value to natural resources like hydrological services, clean air, healthy soils, and living organisms –may be key to preserving these services.

Here’s an example: 53% of the United States’ surface-derived drinking water comes from forests in the country’s upper watersheds. The Forest Service can show that protecting and improving the health of those forests maintains is critical to providing freshwater for hundreds of millions of people. This, in turn, can be translated into terms downstream water-users and policymakers can understand.

However, it’s not always that simple. “It’s really hard to capture how you place that value,” said Dr. Bartuska. “How do you build it into a process?” Often, people are so far removed from forests they have difficulty connecting them to the supposedly “free” resources they rely on every day.

SOURCE: Cascades at sunrise – Sergi K.

Reimagining USFS in a Chaotic World

Over the last century, rapid developments in science and technology, shifting land management approaches, and the ravages caused by climate change crisis on local communities are changing the public’s appreciation of the fundamental role forests play in our everyday lives. Though the circumstances have changed, Gifford Pinchot’s guiding principle still holds: to provide the greatest good for the greatest number of people in the long run.

“Get out into your local forests,” said Dr. Bartuska. “Just stop, and look, and see all the diversity. Recognize the value of having trees and shrubs and different bird species.”

Spending time in nature and educating ourselves on the value public lands provide can be the first step toward driving positive change. U.S. citizens can take action to ensure greater ecological stewardship — whether by volunteering time, donating money or through political advocacy.

“There are public land days,” says Dr. Bartuska, “and those are wonderful opportunities for someone to get out on the land, it could be federal, state, or your local park.”

Most importantly, we need to act NOW The Forest Service provides many opportunities to get involved, as do dozens of other leading institutions.

Want to follow in the footsteps Teddy Roosevelt, Gifford Pinchot, and Aldo Leopold? Get out into our public forests and become a Climate Actionist today!

The founding of the National Forest System and the Forest Service, an agency of the U.S. Department of Agriculture, has its roots in the last quarter of the 19th century

@timmossholder

Did you know?

53 percent of our nation’s surface water supply originates on forest land

US Public Lands Management Entities

The Bureau of Land Management (BLM)

Sustain the health, diversity, and productivity of public lands for the use and enjoyment of present and future generations.

BLM manages one in every 10 acres of land in the United States, and approx. 30% of the Nation’s minerals. These lands and minerals are found in every state in the country and encompass forests, mountains, rangelands, arctic tundra, and deserts.

BLM promotes multiple-use on public lands. These uses include renewable and non-renewable energy development; livestock grazing; mining; logging; outdoor recreation; and conserving natural, historical and cultural resources.

United States Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS)

Working with others to conserve, protect, and enhance fish, wildlife, plants, and their habitats for the continuing benefit of the American people.

Over 150 million acres that include 560+ national wildlife refuges, waterfowl production areas and small wetlands.

FWS manages land to protect endangered species, uphold wildlife laws, manage migratory birds, restore fisheries, and conserve and restore wildlife habitat. FWS manages the country’s National Wildlife Refuge System and contributes to international conservation efforts.

National Park Service (NPS)

Preserves the natural and cultural resources and values of the National Park System for the enjoyment, education, and inspiration of this and future generations.

NPS manages 423 areas (over 85 million acres) in every state, the District of Columbia, American Samoa, Guam, Puerto Rico, and the Virgin Islands. These areas include national parks, monuments, battlefields, military parks, historical parks, historic sites, lakeshores, seashores, recreation areas, scenic rivers and trails, and the White House.

Lands managed by the NPS are used for recreation, education, scholarship, and the preservation of threatened landscapes, ecosystems, and species.

United States Forest Service (USFS)

Sustain the health, diversity, and productivity of the Nation’s forests and grasslands to meet the needs of present and future generations.

USFS manages 193 million acres of public land: 154 national forests, 20 national grasslands, 80 experimental forests and ranges, more than 158,000 miles of trails and 5,000 miles of wild and scenic rivers.

USFS manages forests and grasslands for multiple uses, such as timber harvesting, mineral extraction, outdoor recreation, habitat restoration and rangeland grazing.

RELATED ARTICLES:

Become a Climate Actionist

#climateactionist

One of the first things you do to start your Climate Actionist journey is connect with, engage with, and even join leading climate organizations. At The Copernicus Project, we are committed to only sharing information and resources from organizations, experts, companies, communities, and people that we have personally researched and trust. The following list is a great place to start.

In the coming weeks and months, we’ll have more ways for all of us to be actively involved in finding and supporting nature-based climate solutions. So stay tuned and sign up below to get notifications when we publish new content.