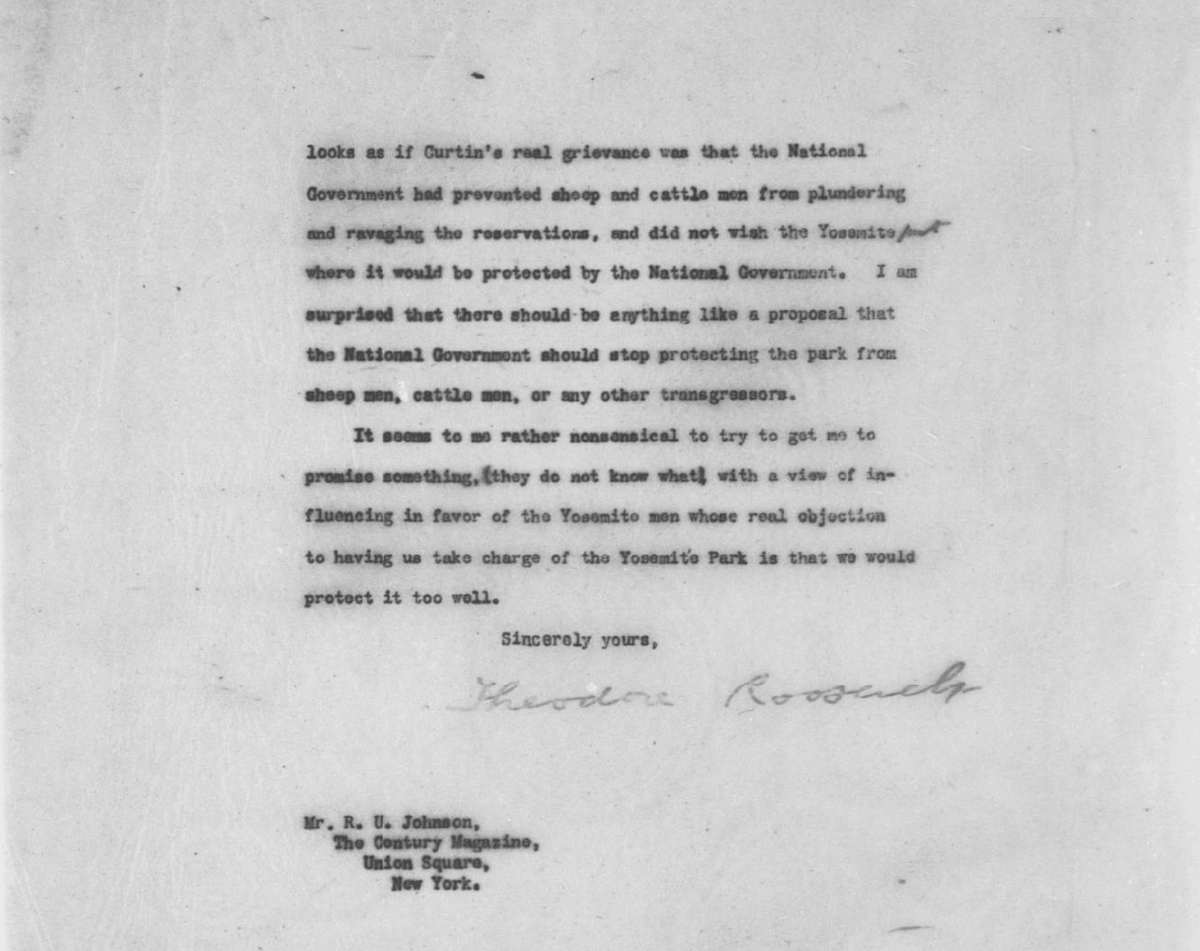

TEDDY ROOSEVELT: CONSERVATIONIST IN CHIEF

“The natural resources of our country are in danger of exhaustion if we permit the old wasteful methods to continue.”

Theodore Roosevelt, from his 1908 speech: “Conservation as a National Duty”

In 1908, Theodore Roosevelt stood before a conference of State governors, natural resource experts and top government officials to mobilize bold and immediate action. His speech, “Conservation as a National Duty”, proclaimed “the weightiest problem now before the Nation…lies in the fact that the natural resources of our country are in danger of exhaustion if we permit the old wasteful methods of exploiting them longer to continue.”

Roosevelt argued forcefully that conservation was a moral obligation to society and future generations: “We are on the verge of a timber famine in this country, and it is unpardonable for the Nation or the States to permit any further cutting of our timber . . . As a people we have the right and the duty, second to none other but the right and duty of obeying the moral law, of requiring and doing justice, to protect ourselves and our children against the wasteful development of our natural resources.”

Theodore Roosevelt, 26th President of the United States in his private office, White House, Washington, D.C. 1903 IMAGE: Library of Congress

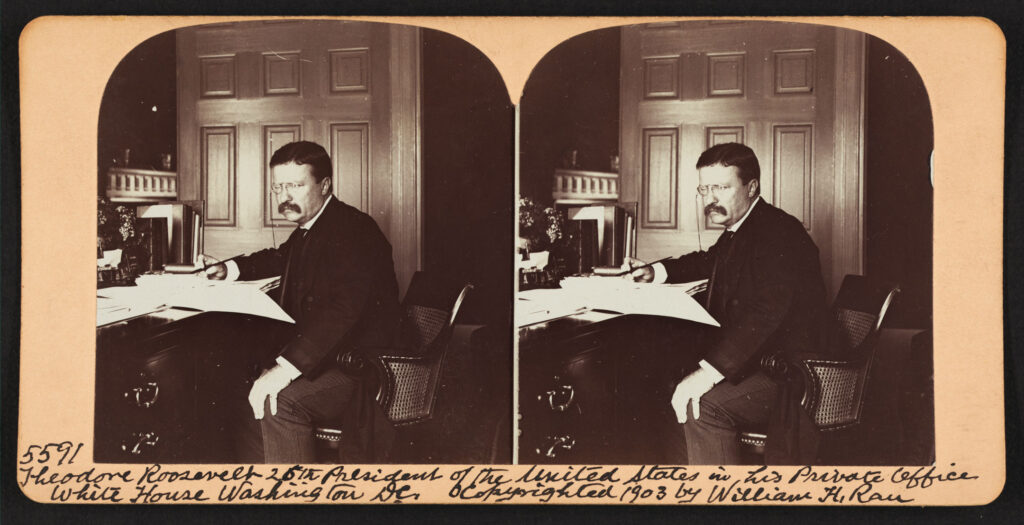

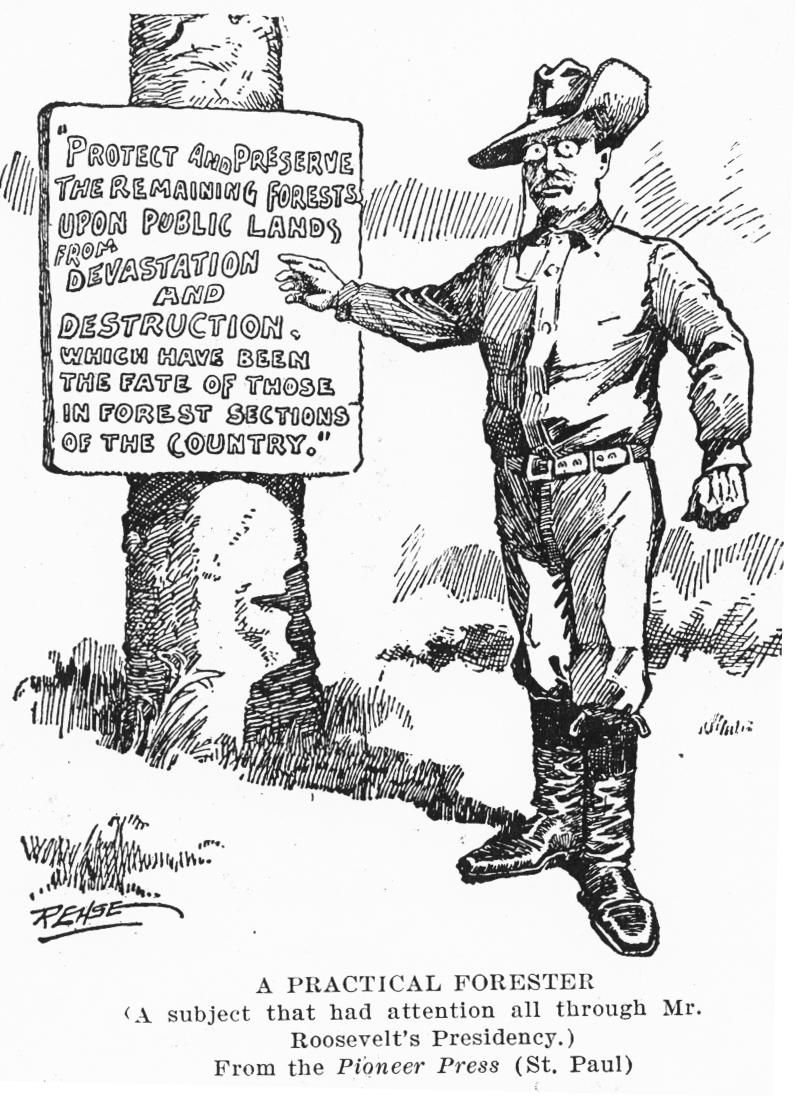

Between 1901 and 1909, despite fervent opposition, Roosevelt placed over 230 million of lands under federal protection. He created the Fish and Wildlife Service, saved some of our most popular national monuments, including the Grand Canyon, from commercial exploitation and laid the groundwork for the National Park Service. He set aside more federal forests, parks and nature preserves than all his predecessors combined.

Nature preservationists like John Muir fought to keep our largest forests intact, free from commercial development. Roosevelt argued instead that large tracts of the nation’s forests, soils, and waterways should benefit society overall – for agriculture, timber, hunting, recreation, scenic beauty, and an array of other uses.

Public forests needed to be actively managed for their long-term ecological health to “make the forest produce the largest amount of whatever crop or service will be most useful and keep on producing it for generation after generation of men and trees.” This might require individual sacrifice in the near-term but, in Roosevelt’s eyes would do the most good for society over the long run.

As a child, young “Teedy” appeared an unlikely candidate for higher office — let alone a Dakota cattle rancher, big game hunter, and “Rough Rider” who led a U.S, cavalry unit in Cuba. Roosevelt was frail, near-sighted, and suffered from debilitating asthma. But his fascination with the natural world began almost as soon as he could walk.

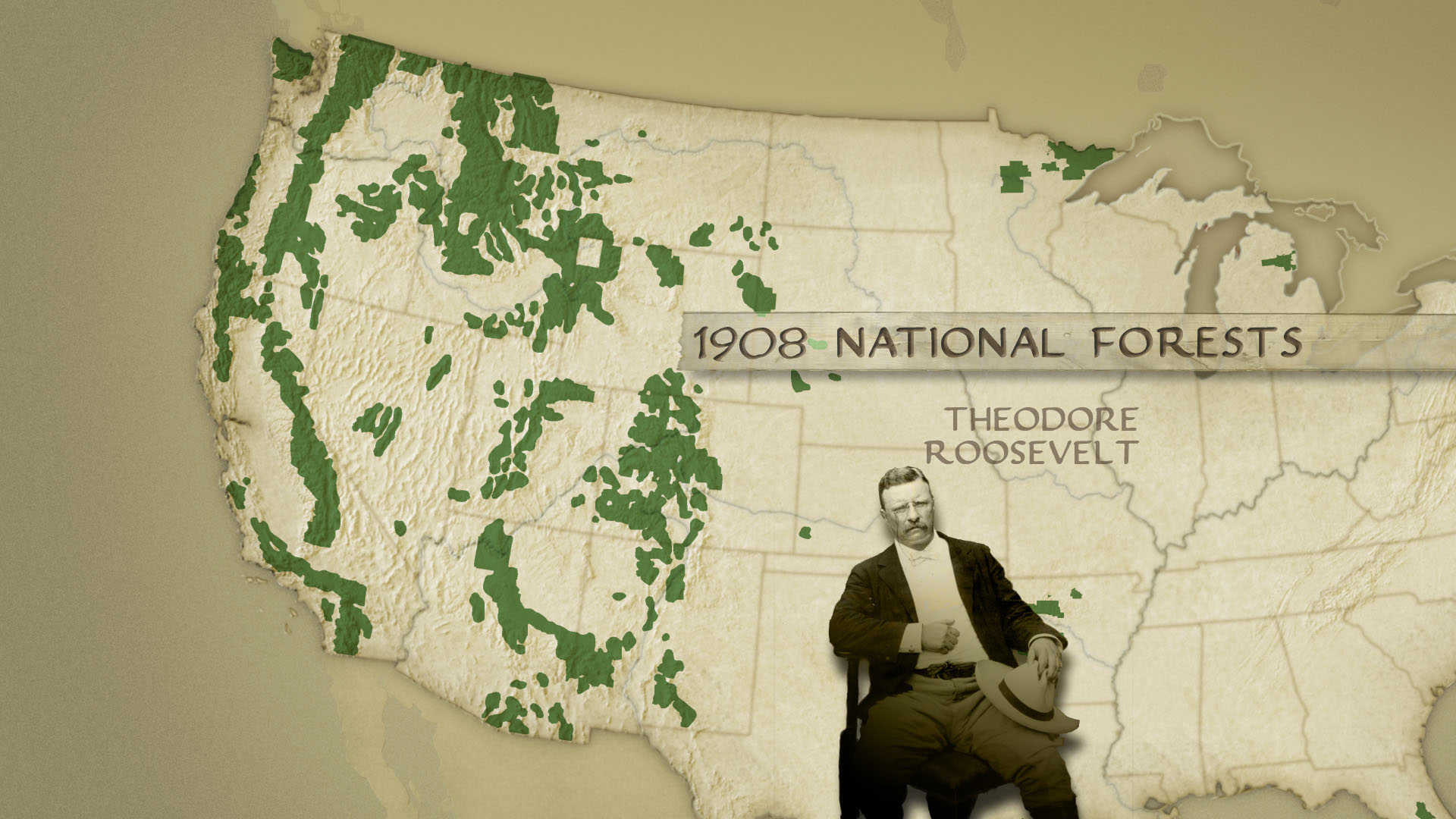

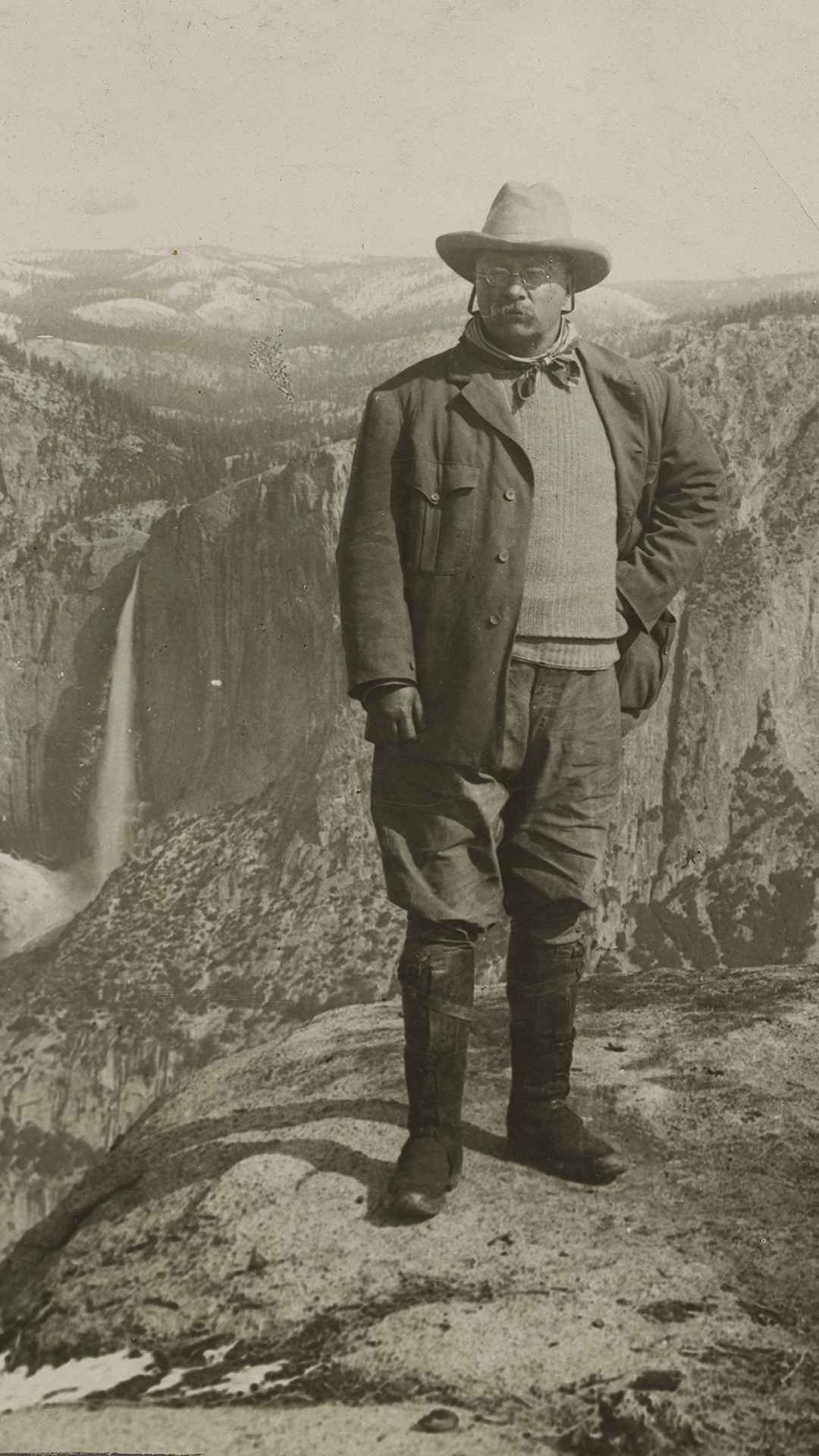

President Roosevelt and John Muir at Yosemite National Park in 1903. IMAGE: Courtesy of the Library of Congress

Roosevelt loved to collect all manner of flora and fauna, proudly displaying some of his favorite specimens in “Roosevelt’s Natural History Museum” at home. After he died, New York State turned a wing of the American Natural History Museum into a two-story Roosevelt Memorial, recognizing the major contributions he made to understanding and protecting the natural world.

Roosevelt’s connection to nature was deeply personal, spiritual, and action-oriented. He ventured into the wilderness to overcome fear, recover from personal tragedy, write books, and contemplate deeply how to improve himself and the world around him.

Witnessing firsthand the alarming destruction of nature, Roosevelt decided the best way to protect his first love was run for public office. He was a leader and a fighter, unafraid to take on and regulate the rapacious, short-sighted corporate excesses and expansion of the Industrial Age.

STARTING FOR CAMP

Image: From a stereograph, 1905, Underwood and Underwood

Roosevelt was also part of an elite coterie of prominent men who founded the modern conservation movement: George Bird Grinnell, Gifford Pinchot, Aldo Leopold, William Hornaday, John Muir, John Burroughs and many others. Thanks to them, vast swaths of the country have been protected and iconic species like the American Bison, antelope, bald eagles, manatees, and elk survive in plentiful numbers.

During his lifetime Roosevelt could never have anticipated the grave threat of climate change caused by rising greenhouse gas emissions. Nor could he have understood the crucial role that forests, grasslands, wetlands and other ecosystems that he fiercely advocated for play in sequestering and storing carbon.

But his repeated admonitions to limit the wasteful use of non-renewable resources like coal, iron, and natural gas and his foresight to set aside nearly a third of the country to serve as renewable “carbon banks” were farsighted indeed.

Following his example, perhaps we too will realize we have the right and duty to protect ourselves and our children against the wasteful development of our natural resources.

ROOSEVELT’S LEGACY

During Roosevelt’s administration, the National Park System grew substantially. When the National Park Service was created in 1916 – seven years after Roosevelt left office – there were 35 sites to be managed by the new organization. Roosevelt helped create 23 of those.

See below for a list of the sites created during his administration which are connected with the National Park Service.

National Parks

National parks are created by an act of Congress. Before 1916, they were managed by the Secretary of the Interior. Roosevelt worked with his legislative branch to establish these sites:

- Crater Lake National Park (OR) – 1902

- Wind Cave National Park (SD) – 1903

- Sullys Hill (ND) – 1904 (now managed by USFWS)

- Platt National Park (OK) – 1906 (now part of Chickasaw National Recreation Area)

- Mesa Verde National Park (CO) – 1906

- Added land to Yosemite National Park (CA)

National Monuments

Roosevelt signed the Act for the Preservation of American Antiquities – also known as the Antiquities Act or the National Monuments Act – on June 8, 1906. The law gave the president discretion to “declare by public proclamation historic landmarks, historic and prehistoric structures, and other objects of historic and scientific interest… to be National Monuments.”

Since he did not need congressional approval, Roosevelt could establish national monuments much easier than national parks. He dedicated these sites as national monuments:

-

Devil’s Tower (WY) – 1906

-

El Morro (NM) – 1906

-

Montezuma Castle (AZ) – 1906

-

Petrified Forest (AZ) – 1906 (now a national park)

-

Chaco Canyon (NM) – 1907

-

Lassen Peak (CA) – 1907 (now Lassen Volcanic National Park)

-

Cinder Cone (CA) – 1907 (now part of Lassen Volcanic National Park)

-

Gila Cliff Dwellings (NM) – 1907

-

Tonto (AZ) – 1907

-

Muir Woods (CA) – 1908

-

Grand Canyon (AZ) – 1908 (now a national park)

-

Pinnacles (CA) – 1908 (now a national park)

-

Jewel Cave (SD) – 1908

-

Natural Bridges (UT) – 1908

-

Lewis & Clark Caverns (MT) – 1908 (now a Montana State Park)

-

Tumacacori (AZ) – 1908

-

Wheeler (CO) – 1908 (now Wheeler Geologic Area, part of Rio Grande National Forest)

-

Mount Olympus (WA) – 1909 (now Olympic National Park)

Roosevelt also established Chalmette Monument and Grounds in 1907, a site of the Battle of New Orleans. It is now a part of Jean Lafitte National Historical Park.

Theodore Roosevelt and the National Park System

Crater Lake, Oregon; Wind Cave, South Dakota; Sullys Hill, North Dakota; Mesa Verde, Colorado; and Platt, Oklahoma.

Theodore Roosevelt, as President from 1901 to 1909, signed legislation establishing five new national parks: Crater Lake, Oregon; Wind Cave, South Dakota; Sullys Hill, North Dakota (later re-designated a game preserve); Mesa Verde, Colorado; and Platt, Oklahoma (now part of Chickasaw National Recreation Area).

By the end of his term he had reserved six predominantly cultural areas and twelve predominantly natural areas; Devils Tower (Wyoming), El Morro (New Mexico), Montezuma Castle (Arizona), and Petrified Forest (Arizona), and a large portion of the Grand Canyon (Arizona).

“We are prone to speak of the resources of this country as inexhaustible; this is not so.”

-Theodore Roosevelt, seventh annual message to Congress, Dec. 3, 1907.

On May 13, 1908, President Theodore Roosevelt delivered the opening address, “Conservation as a National Duty,” at the outset of a three-day meeting billed as the Governors’ Conference on the Conservation of Natural Resources.

Outdoor pastimes of an American hunter

by Theodore Roosevelt 1908

The Wilderness Warrior: Theodore Roosevelt and the Crusade for America

From New York Times bestselling historian Douglas Brinkley comes a sweeping historical narrative and eye-opening look at the pioneering environmental policies of President Theodore Roosevelt, avid bird-watcher, naturalist, and the founding father of America’s conservation movement.

In this groundbreaking epic biography, Douglas Brinkley draws on never-before-published materials to examine the life and achievements of our “naturalist president.” By setting aside more than 230 million acres of wild America for posterity between 1901 and 1909, Theodore Roosevelt made conservation a universal endeavor.

RELATED ARTICLES:

Become a Climate Actionist

#climateactionist

One of the first things you do to start your Climate Actionist journey is connect with, engage with, and even join leading climate organizations. At The Copernicus Project, we are committed to only sharing information and resources from organizations, experts, companies, communities, and people that we have personally researched and trust. The following list is a great place to start. We’ve broken it out by category, so you can hone in on the things you are most interested in.

In the coming weeks and months, we’ll have more ways for all of us to be actively involved in finding and supporting nature-based climate solutions. So stay tuned and sign up below to get notifications when we publish new content.