“Nature is central to our emotional, physical, and spiritual wealth and well-being.”

– Laurie Wayburn, Pacific Forest Trust

Putting the Forests Back Into Forestry

How making money and protecting the places we love can lead to win-win conservation outcomes.

We lose roughly 1,900 square miles of forest each year to logging, an area the size of Delaware. Fortunately, good stewardship of privately owned forests—which make up 56% of forested land in the U.S.—can go a long way in preventing deforestation and forest degradation.

To learn more about private forests and how best to protect them, we sat down with Laurie Wayburn, co-founder and CEO of the Pacific Forest Trust (PFT). The Pacific Forest Trust was founded in 1993 as a conservation land trust. Its goal was to partner with private landowners to help them manage their forests for long-term conservation values and not degrade them through over-harvesting, commercial development, or other destructive activities.

Laurie and her co-founder, Connie Best, started PFT because they realized that most conservation programs at that time focused mainly on protecting old-growth forests. Preserving old-growth forests is critical, but there are very few of them left. According to Laurie, less than 1% of U.S. forests are considered true old-growth.

In 2001, Laurie and Connie wrote a book titled America’s Private Forests, which provided the first comprehensive analysis of the essential role played by privately owned forests. Their research showed the biggest forest losses, by far, were taking place on private lands. Wayburn and Best also highlighted the tremendous conservation potential available in private forests, and illustrated how conservation easements can be a key tool to protect these forests for generations to come.

When people think about forest conservation, they often envision the government telling them what they can and cannot do on their land. Conservation easements turn this way of thinking on its head. Easements give landowners a tax-advantaged way to use their land the way they want to use it — as long as they enhance its long-term conservation values, thereby creating a benefit for the public.

Land trusts like the Pacific Forest Trust help people get paid to do what they want to do: generate income from their land while protecting it in perpetuity.

To learn more about conservation easements, take a DEEP DIVE ON CONSERVATION EASEMENTS

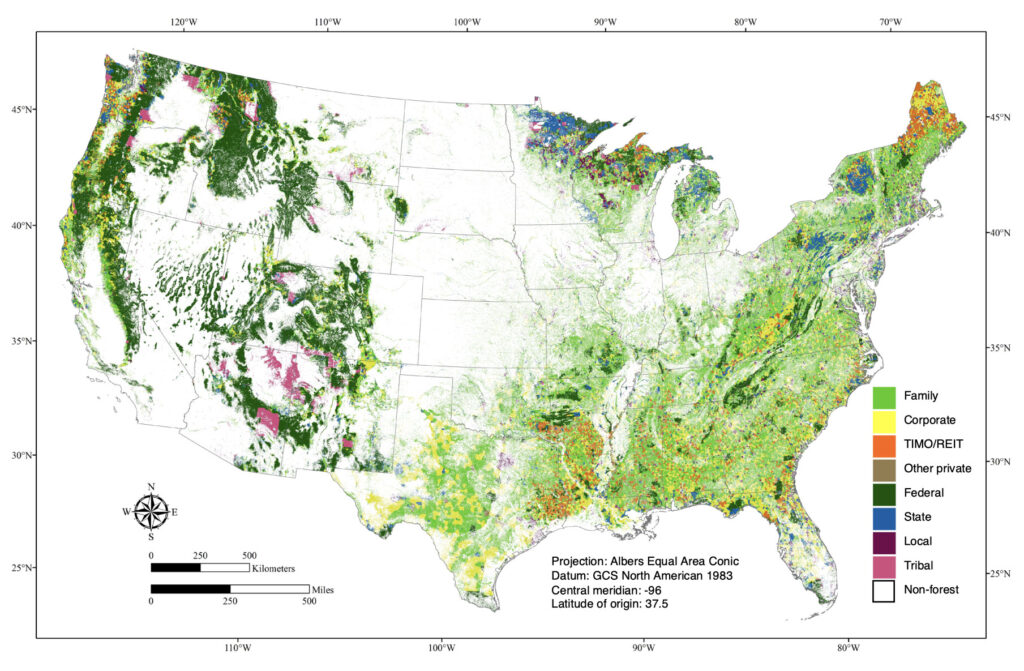

The roughly 800 million acres of forests and woodlands in the United States are owned by government agencies, corporations, tribal leaders, cities, and a wide array of private landowners. Family-owned forests account for roughly 40 percent of the total.

USDA Forest Service: Forest ownership, United States, 2017 (Sass et al. 2020). The underlying data for this map were collected between 2012 and 2017.

Non-industrial private owners hold over 300 million acres of land. Roughly half of that is held by individual owners with less than 100 acres. Larger landowners, with more than 500 acres, control just under 15 percent.

It might sound impossible to get a group of such radically different owners to do anything in concert, but Laurie tells us that “all landowners are aware there is a financial value to their forests, and that awareness is going to be an aspect that drives their decision-making. Whether they’re a family or a corporation, making money is a concern, and it’s a totally legitimate concern.”

And that’s not the only tie that binds this diverse groups of landowners. According to Laurie, “Almost all landowners are also motivated by legacy and their love of the land.”

All landowners are aware there is a financial value to their forests and that awareness is going to be an aspect that drives their decision-making

If you need money to maintain ownership of the land, that may be the determining factor in your decision. This is particularly true for corporations and investors who need to show financial returns and generate positive cash flow.

Motivations for protecting forests run the gamut: There are individual landowners who want to preserve their lands for their heirs. Others need additional funds to be able to afford owning and maintaining their property. Tribal leaders often see forests as part of their ancestral heritage. Corporations and investors may need to generate income but truly love the land and want to preserve it.

Core to what the Pacific Forest Trust and other land trusts do is showing landowners how conservation is in their own best interests, both economically and emotionally. Utilizing tools like conservation easements mean landowners can make money from their land, without turning it into a subdivision or generating income from destructive logging and mineral extraction.

This may mean keeping the land as it is, not only for one’s own legacy, but for the wildlife that needs safe passage, the watersheds that flow through it, for the hunting and fishing, scenic beauty, and more.

The founder of The Copernicus Project, Jack Stephenson, is part-owner of ranchland passed down by his great grandfather. In the 1990’s his family set up a conservation easement that allows for a few limited uses: maintaining existing cabins, hiking, hunting, fishing and grazing cattle. The easement significantly reduced the value of the land and generated a sizeable tax break. Stephenson tells us being a good steward of the land also means being a good neighbor and member of the community—core to the fabric of many rural areas.

When it comes to international forest policy, the United Nations has included protection of global forests in its global climate treaties. Participants laid out specific measures to protect forests as part of the Kyoto Protocol in 1997.

“All the focus was on going carbon neutral and getting to net zero emissions—both important things to focus on—but they skipped over the fact that the loss of forests accounts for 40% of the accumulated CO2 in our atmosphere.”

Unfortunately, Laurie explains, the narrative quickly shifted and “all the focus was on going carbon neutral and getting to net zero emissions”—both important things to focus on—but they “skipped over the fact that the loss of forests accounts for 40% of the accumulated CO2 in our atmosphere.”

Given the vast amounts of carbon that forests sequester and store each year, protecting intact healthy forests is essential to fighting climate change.

Whether you own land or not, there are many things we can do as Climate Actionists to fulfill the Pacific Forest Trust’s goal of “putting the forest back in forestry”.

From showing up at city and county meetings, to approaching landowners in our local communities, to connecting with elders and councils, we can actively support private property owners who want to conserve their forests instead of degrading them.

In our everyday lives we can become much more selective in our own consumption of forest products: When you purchase products made from wood, do you check to see if they are sustainably sourced? A large assortment of ecologically oriented products is readily available in stores and online.

Green forests, green dollars to help landowners protect their land, and green personal choices can go a long way toward protecting and restoring one of the most fundamental parts of our natural heritage: large expanses of healthy forests.

America’s Private Forests

Status and Stewardship

This book, written by Constance Best and Laurie Wayburn, the co-founders of Pacific Forest Trust, examines private forests in the U.S. It presents research, data, and analyses of the current state of America’s forests. Complete with an action plan for protecting private forests, this book offers specific recommendations to accelerate the conservation of privately owned forestlands.

“Being a good steward of the land also means being a good neighbor and community member”

– Laurie Wayburn, Pacific Forest Trust

RELATED ARTICLES:

Become a Climate Actionist

#climateactionist

One of the first things you do to start your Climate Actionist journey is connect with, engage with, and even join leading climate organizations. At The Copernicus Project, we are committed to only sharing information and resources from organizations, experts, companies, communities, and people that we have personally researched and trust. The following list is a great place to start. We’ve broken it out by category, so you can hone in on the things you are most interested in.

In the coming weeks and months, we’ll have more ways for all of us to be actively involved in finding and supporting nature-based climate solutions, so stay tuned and sign up below to get notifications when we publish new content.