Community organizations like Friends of the Bay use well-informed management strategies to protect the health of local watersheds

OYSTER BAY: A MODEL FOR THE FUTURE OF WATERSHED RESTORATION

Mitch Kramer starts his day early. Our leisurely 8:30 AM arrival at the dock gave him time to tend to his cell phone, which never stops ringing. On the other end of the line, customers and colleagues (including Oyster Bay residents, commercial fishermen, and, once in a while, a guy named Billy Joel) chat with him about the day ahead.

Morning light glints off the surface of the water being agitated by jumping red snappers. A white egret streaks across the bright blue sky. A few yards offshore, we hear a rustling from the lofty perch of an osprey nest: fledglings awaiting their breakfast.

Soon Mitch is waving us down the dock, and it’s time to go.

Mitch has lived in the town of Oyster Bay all his life and spent his career on the water, owning and operating his company, North Shore Towing and Diving. For thirty years, Mitch has provided services to the local community. His lifelong love of the water set his career path at a young age. “I had a boat when I just started walking,” he tells us.

Sea Grass in August, West Harbor, Oyster Bay, NY

Moments later, we’re zooming out onto the bay, skipping like a stone over the glassy surface of the water. Portions of the bay’s shoreline remain undeveloped, but those forested stretches are interrupted by mansions, roadways, and marinas. Out on the water, one can only imagine what the view must have looked like centuries ago: 360 degrees of panoramic wilderness.

Since its development, Oyster Bay has faced numerous environmental challenges. In 1987, a small group of locals became concerned about the potential impact of a development project at the Jakobson Shipyard site on the Oyster Bay waterfront. The group, led by a clammer and a local mayor, formed Friends of the Bay — a non-profit that works to protect and restore the health of the Bay.

Developers had planned to construct a restaurant, hotel, and marina on the waterfront. Not only would this destroy the shoreline, it would endanger native marine life, most notably its oysters.

Throughout the 19th and early 20th centuries, the oyster industry boomed in the Long Island Sound and Great South Bay. In 1860, some 12 million oysters were sold in New York markets; by 1880, the area’s oyster beds were producing 700 million a year.

Sixty years later, the Jakobson Shipyard development project threatened to close the last remaining oyster company on Long Island, imperiling the livelihoods of its staff and independent oystermen. Although local officials supported the development, Friends of the Bay generated public opposition by educating Oyster Bay residents about the project’s potential impacts.

By 1990, the project was defeated.

Today, thirty people sit on the board of Friends of the Bay, including Mitch, who serves as Vice President. His lifelong career on the water and devotion to his hometown inspired him to give back.

In the age of climate change, Oyster Bay faces entirely new challenges, including rising water temperatures and increased frequency and intensity of storms. Changing environmental conditions have triggered increases in erosion and sedimentation, stormwater runoff, algal blooms, habitat loss, and non-native species. Each of these threats disrupts the bay’s ecology in different ways.

“Let’s take the last five or six years. We’ve definitely noticed that the storms have been worse, and the types of storms we get have changed drastically from what I remember,” said Mitch. “There’s a lot of erosion. We’ve seen higher tides play a big role on the shoreline and the shore grasses. We’ve also seen a lot of different species that we’re not used to here.”

He goes on; “We had beluga whales come into the harbor a while ago. Last year we had a whale that ended up passing away in Oyster Bay. We now have seals that come in every year, they’re here all the time. People look at that and say “wow, how cool is that”? I look at it like, “why are they here?”

Changing environmental conditions have triggered increases in erosion and sedimentation, stormwater runoff, algal blooms, habitat loss, and non-native species. Each of these threats disrupts Oyster Bay’s ecology in different ways.

To learn more about how Friends of the Bay is managing these emerging threats, we sat down with their executive director, Heather Johnson.

“The oyster population has plummeted precipitously,” she told us. This is due to a number of factors, but the potential link between climate effects and oyster declines does not go unnoticed. Heather cites predation, degraded water quality, and overharvesting as the main factors that influence oyster populations. However, “There’s a lot of opinion and not enough data,” she said.

Back in 2005, the Oyster Bay National Wildlife Refuge made Defenders of Wildlife’s annual list of the ten most endangered wildlife refuges in the country. DoW identified polluted stormwater runoff, habitat destruction, unsustainable development, and human sewage as the main threats to the refuge.

Four years later, Friends of the Bay published their State of the Watershed report, which summarizes the health of Oyster Bay and Cold Spring Harbor. The report echoes both Heather’s opinion and the DoW decision. It explains that pollution threatens water quality, while development pressure reduces the amount of available habitat and increases “impervious surfaces” in the watershed, which includes any hard surface that prevents rainfall from infiltrating underlying soils or groundwater. Additionally, construction of man-made dams and culverts inhibits fish passage along streams.

It will come as no surprise that these threats have impacted industry and recreation on Oyster Bay. The report states that impairments to shell fishing, public bathing, fish consumption, habitat, and aquatic life have been identified for parts of the harbor complex.

This is especially bad news for oysters. The Frank M. Flower & Sons, Inc shellfish company, along with more than 80 independent commercial baymen, annually harvests up to 90% of New York’s oyster crop from the heart of the Oyster Bay National Wildlife Refuge. Historically, most of the waters of Oyster Bay have been classified with the best water quality for shell fishing – an unusual distinction given its proximity to New York City and the fact that the harbors to the west have been closed for more than 30 years. Now, as the detrimental effects of development and pollution become further complicated by climate change, this industry faces major challenges.

Friends of the Bay, Taking Action

Friends of the Bay is working hard to combat these issues. “We have a long-term water quality monitoring program that’s in its twenty-second year,” said Heather. The program looks at factors such as water temperature, pH, salinity, and dissolved oxygen concentrations in order to assess water quality. FOTB also organizes beach cleanups, which unify the local community around stewardship of Oyster Bay.

“In February 2019, we started our monthly beach cleanup program and we had 15 people who showed up,” said Heather. “It was freezing cold, but it goes to show you how dedicated people can be. In the past year, we’ve cleaned up 600 pounds of trash from our shores thanks to volunteers. Not only are we removing trash, but we’re engaging a whole other group of volunteers that we didn’t have before, and it’s really heartening to see that.”

Mitch is hopeful, too. Restorative aquaculture is emerging as a viable environmental remediation strategy in Oyster Bay.

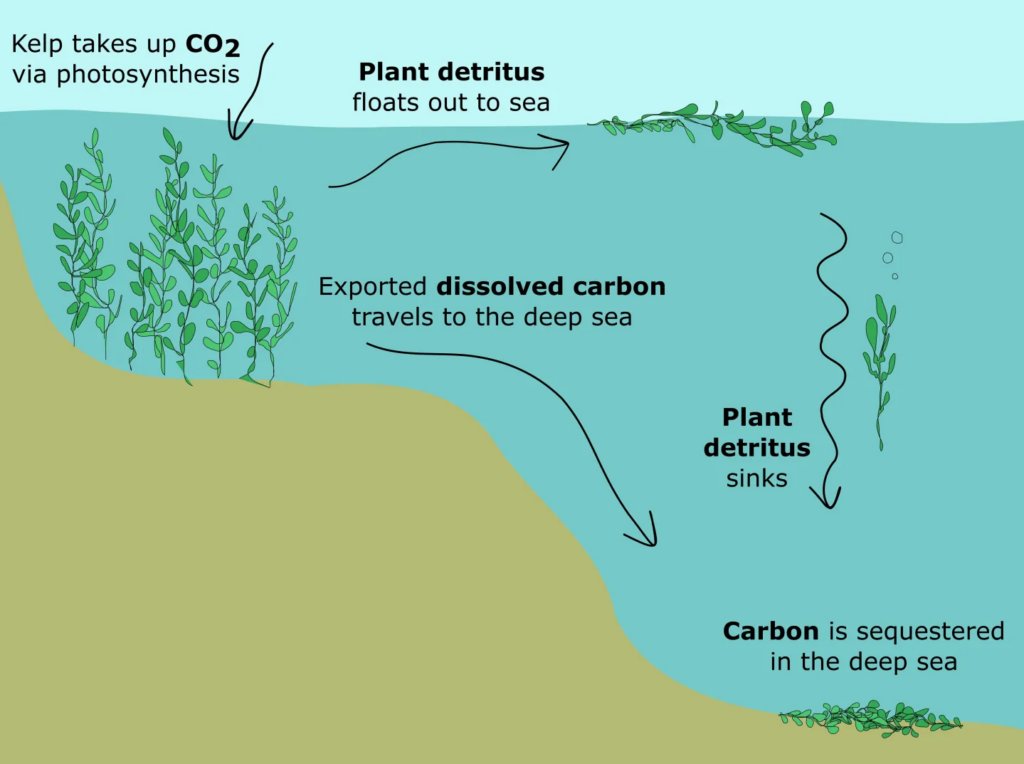

“There are natural things we can do,” he explained. “One of them is protecting and restoring the shellfish, they filter the water. We’ve also gotten into farming kelp, which absorbs the nitrogen.”

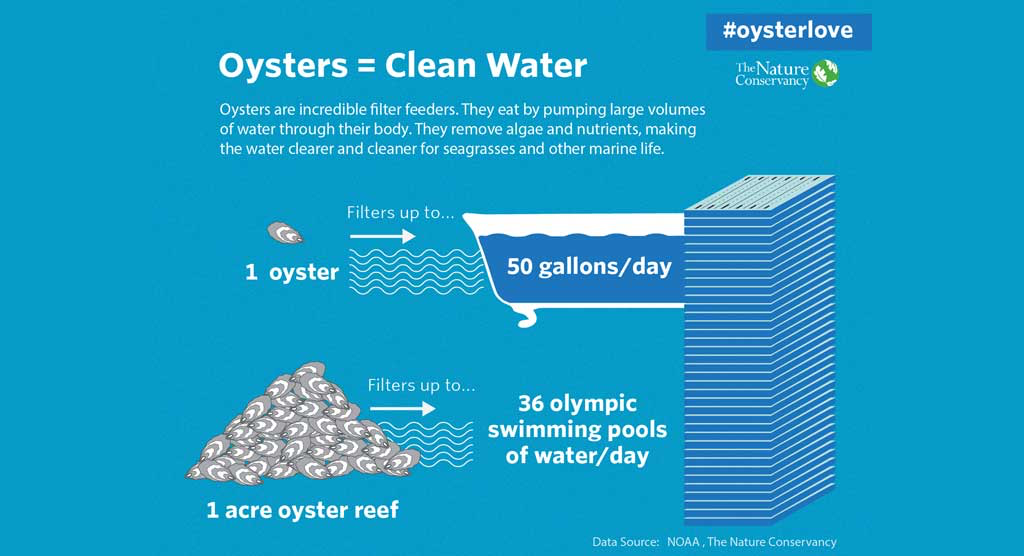

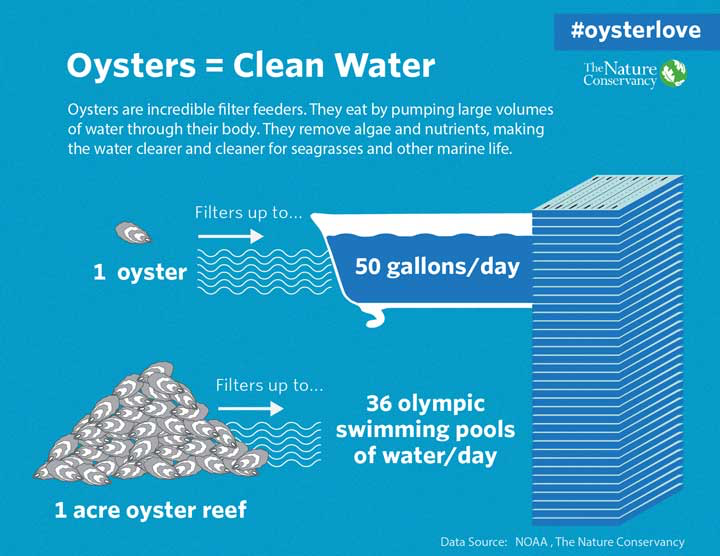

An adult oyster can filter up to 50 gallons of water per day simply through feeding. Kelp farming not only remediates nutrient pollution to prevent algal blooms, but can also sequester carbon.

Coastal ecosystems sequester surprisingly large amounts of carbon: up to 20 times more carbon per acre than forests. However, as global warming, pollution, and development degrade these critical ecosystems, their sequestration potential decreases. Protecting and restoring places like Oyster Bay is not only good for recreation, industry, and aesthetics, it allows the watershed to serve as an active climate solution.

Kelp farming not only remediates nutrient pollution to prevent algal blooms, but can also sequester carbon.

The first step is getting the community engaged. “If you take even five minutes to go out into the estuary and see its beauty, and if you know the importance of this area, then I don’t know how anybody could not want to work to protect it,” said Heather.

Out on the water with Mitch, anyone can appreciate Oyster Bay’s critical importance to the local community and environment. “Get involved with local organizations,” he said. “There are a lot more volunteer opportunities. There have always been volunteer organizations, but now, a lot of these organizations are doing things that are directly impacting the bay.”

Over the last century, Oyster Bay has withstood incredible pressure, pressure that is mounting as climate change ushers us into an age of uncertainty. Empowering community organizations like Friends of the Bay to lead conservation efforts is critical to the health of our nation’s watersheds.

Want to get involved with Friends of the Bay?

Here’s how:

Sign up for event notifications to stay in the loop on FOB events and volunteer opportunities!

Click here to see an up-to-date list of FOB beach cleanup days!

To become a FOB volunteer, register here!

Can’t get to Oyster Bay? No problem! You can help protect coastal marine ecosystems in YOUR area:

Find a beach cleanup near you with Ocean Conservancy’s interactive map!

To learn how to start a coastal restoration project in your community, check out this toolkit!

This ArcGIS storymap can help you learn about how and where coastal marine ecosystems store carbon!